Rambling About UVM Factory Overrides - Per Instance

In the previous post we looked at how we can use the factory to direct an existing test by changing the type of sequence items that get created by that test’s sequence. The UVM factory’s type override mechanism is indispensable in achieving this degree of flexibility. For small designs with interfaces of different kinds, type overrides are sufficient, but once we start talking about DUTs with two or more interfaces of the same type, we will immediately run into limitations.

Let’s take the design from last time (the simple AHB slave) and give it another AHB interface. As we did before, we’ll look at the e verification environment first. We need to instantiate another agent for this new interface. At the same time we want to be able to differentiate between the two pairs. The e way of doing this is to add an enumerated field to the agent, to the sequence driver and to the BFM that identifies who is who:

<'

type ahb_inst_t : [ AHB0 ];

unit ahb_bfm {

inst : ahb_inst_t;

// ...

};

extend ahb_sequence_driver {

inst : ahb_inst_t;

};

unit ahb_agent {

inst : ahb_inst_t;

// ...

keep driver.inst == inst;

keep bfm.inst == inst;

};

'>

Typically, the eVC developer will have already defined this infrastructure for us by defining the inst_t type with only one literal (AHB0) and the fields inside the eVC units. When wanting to instantiate something a second, third, etc. time we as eVC users would extend the inst_t type and add a new literal per desired instance (in our case AHB1):

<'

extend ahb_inst_t : [ AHB1 ];

'>

We can now instantiate our eVC components:

<'

extend sys {

ahb0 : AHB0 ahb_agent is instance;

ahb1 : AHB1 ahb_agent is instance;

};

'>

The fully random test looks exactly the same as last time:

<'

import env;

extend MAIN ahb_sequence {

!item : ahb_item;

keep count in [ 10..20 ];

body() @driver.clock is only {

for i from 1 to count {

do item;

};

};

};

'>

A separate MAIN sequence will get started on each of the two drivers and push traffic to both AHB interfaces. This test could be the only one we’ll ever write and if run often enough it will thoroughly stress the design. We know from last time, though, that this isn’t terribly efficient, since we usually know where the sweet spots for finding bugs are and we’d like to check those as soon as possible.

Let’s assume that our device implements some kind of prioritization scheme where writes on the first AHB interface can stall reads on the second. This is something we could immediately check by refining our test:

<'

import test1;

extend ahb_item {

keep driver.inst == AHB0 => direction == WRITE;

keep driver.inst == AHB1 => direction == READ;

};

'>

Each item knows from its parent driver to which interface it belongs to. We can use this information to constrain the direction of the accesses.

Following the same example, we can add the constraint that all items on interface 0 should come one after the other, while the ones on interface 1 can take their time:

<'

import test2;

extend ahb_item {

keep driver.inst == AHB0 => delay == NONE;

keep driver.inst == AHB1 => delay == LARGE;

};

'>

Our designers still tell us that the device does some magic with byte transfers, which is, of course, something we want to check immediately. We could easily write a test that constrains all items, regardless of the interface they belong to, to be byte accesses. In fact it’s so easy, that we’re not going to do it here. What’s more interesting is verifying what happens with the prioritization scheme when only bytes get transferred. On top of the implication constraints for each each instance, we can add another universal constraint to make all accesses one byte wide:

<'

import test2;

extend ahb_item {

keep size == BYTE;

};

'>

As we can see, it’s easy to mix and match constraints that apply only to one interface with those that apply to both of them.

Let’s investigate the UVM verification environment next. It should be pretty clear already that the factory type override mechanism isn’t going to cut it in this case. We need a mechanism to control the replacement of items based on which AHB interface they belong to. That will come in due time, but first thing’s first, we need to build up our environment:

virtual class test_base extends uvm_test;

ahb_agent ahb0;

ahb_agent ahb1;

function new(string name, uvm_component parent);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

virtual function void build_phase(uvm_phase phase);

ahb0 = ahb_agent::type_id::create("ahb0", this);

ahb1 = ahb_agent::type_id::create("ahb1", this);

endfunction

endclass

We now have two agents, but how do we distinguish between them? This is where the paradigms vary for the two languages. We can’t easily add a new field to identify who is who, because in practice the code for the AHB UVC would be off limits to editing (it is commercial VIP, for example). At the same time, we can’t add literals to SystemVerilog enums and it would be impractical to pre-define a large number of literals for many potential instances. Because of these reasons, the UVM approach is to differentiate component instances by their path.

Our initial test needs to start a traffic sequence on each sequence:

class test1 extends test_base;

`uvm_component_utils(test1)

function new(string name, uvm_component parent);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

virtual function void end_of_elaboration_phase(uvm_phase phase);

uvm_config_db #(uvm_object_wrapper)::set(this, "ahb0.sequencer.run_phase",

"default_sequence", main_ahb_sequence::get_type());

uvm_config_db #(uvm_object_wrapper)::set(this, "ahb1.sequencer.run_phase",

"default_sequence", main_ahb_sequence::get_type());

endfunction

endclass

Now let’s look at the case where we want to drive only writes on the first interface and only reads on the second interface. We could use an item’s parent sequencer’s path inside the constraint, similarly to what we did in e. Since both sequencers are called sequencer we’d need to use the full path to differentiate between them. This isn’t great for vertical reuse. What if we’d later want to reuse these sequence items inside an environment where the paths change because we add an extra level of hierarchy? The constraints will silently refuse to work and we won’t get any compile error.

The way to control this in UVM is to selectively override items based on the path of their parent sequencer. First, we need the two different item flavors:

class write_ahb_item extends ahb_item;

`uvm_object_utils(write_ahb_item)

constraint write {

direction == WRITE;

}

function new(string name = "write_ahb_item");

super.new(name);

endfunction

endclass

class read_ahb_item extends ahb_item;

`uvm_object_utils(read_ahb_item)

constraint read {

direction == READ;

}

function new(string name = "read_ahb_item");

super.new(name);

endfunction

endclass

Now we can specify which items should become write_ahb_items and which ones should become read_ahb_items. We do this using a factory instance override:

class test2 extends test1;

`uvm_component_utils(test2)

function new(string name, uvm_component parent);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

virtual function void end_of_elaboration_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.end_of_elaboration_phase(phase);

ahb_item::type_id::set_inst_override(write_ahb_item::get_type(),

"ahb0.sequencer.*", this);

ahb_item::type_id::set_inst_override(read_ahb_item::get_type(),

"ahb1.sequencer.*", this);

endfunction

endclass

The set_inst_override(…) function takes, in addition to the override type, two arguments that are used to construct the path on which to apply the override. The path of the third component specified as the third argument is prepended to the second argument to create an absolute path. The ”*” at the end instructs the factory to apply this override to all objects created under that scope.

You might have had a realization at this point that sequence items are uvm_objects and don’t have a parent per se (the signature for a uvm_object’s constructor is new(string name = …)). If we supply only a name to create(…), then the object’s name will be the same as its full name:

class some_object extends uvm_object;

`uvm_object_utils(some_object)

function new(string name = "some_object");

super.new(name);

endfunction

endclass

some_object obj = some_object::type_id::create("obj");

A more esoteric feature that isn’t as well known is that it’s possible to also pass a component as an argument to an object’s create(…) function:

some_object obj = some_object::type_id::create("obj", some_component);

This extra argument will let the factory know under which path the object is getting instantiated. It is this path that is compared to see if any instance overrides exist for it and is also called the object’s context. The `uvm_do macro handles that the context for the sequence item being started is set to the sequencer’s hierarchical path. If we weren’t using the sequence macros, we’d need to make sure we set the context of the item we would be creating.

Now that we have our write and read overrides in place, let’s create the next test where we also constrain the timings. As before, we’ll need to define the items:

class fast_write_ahb_item extends write_ahb_item;

`uvm_object_utils(fast_write_ahb_item)

constraint fast {

delay == NONE;

}

function new(string name = "fast_write_ahb_item");

super.new(name);

endfunction

endclass

class slow_read_ahb_item extends read_ahb_item;

`uvm_object_utils(slow_read_ahb_item)

constraint slow{

delay == LARGE;

}

function new(string name = "slow_read_ahb_item");

super.new(name);

endfunction

endclass

We can set up the overrides like we did in the previous test, using set_inst_override(…):

class test3a extends test2;

`uvm_component_utils(test3a)

function new(string name, uvm_component parent);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

virtual function void end_of_elaboration_phase(uvm_phase phase);

ahb_item::type_id::set_inst_override(fast_write_ahb_item::get_type(),

"ahb0.sequencer.*", this);

ahb_item::type_id::set_inst_override(slow_read_ahb_item::get_type(),

"ahb1.sequencer.*", this);

super.end_of_elaboration_phase(phase);

endfunction

endclass

This override will take precedence over the previous one. The UVM developers implemented the factory in such a way that instance overrides get stored in a queue and the first one that matches is the one that gets taken. This is why we need to set up our new overrides before the call to the base class’s method (which adds its own). Why it’s like this I don’t know. I guess it’s to make things more interesting (by making them more complicated, since type overrides work in the opposite way - the last one wins).

The main idea behind storing instance overrides in a queue is that it enables different layers of tweaking. Let’s assume for a second that we have three AHB agents. We want the first one to only start fast writes, while the others should only generate slow reads. We can set this up using only two instance overrides:

class test3b extends test2;

`uvm_component_utils(test3b)

function new(string name, uvm_component parent);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

virtual function void end_of_elaboration_phase(uvm_phase phase);

ahb_item::type_id::set_inst_override(fast_write_ahb_item::get_type(),

"ahb0.sequencer.*", this);

ahb_item::type_id::set_inst_override(slow_read_ahb_item::get_type(),

"*.sequencer.*", this);

super.end_of_elaboration_phase(phase);

endfunction

endclass

Since we know that instance overrides, are matched in the order in which they appear, we have to write the more specific one for AHB0 first. Afterwards, the more generic one can match either AHB1 or AHB2 (if it would exist). Again, why the developers chose to do it like this is beyond me. It would have made much more sense to have it the other way around: do the more generic parts first, followed by the specifics, since writing new tests usually involves doing more and more specialization.

We can also extend our test from the random one and apply the instance overrides to it (like the second test does):

class test3c extends test1;

`uvm_component_utils(test3c)

function new(string name, uvm_component parent);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

virtual function void end_of_elaboration_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.end_of_elaboration_phase(phase);

ahb_item::type_id::set_inst_override(fast_write_ahb_item::get_type(),

"ahb0.sequencer.*", this);

ahb_item::type_id::set_inst_override(slow_read_ahb_item::get_type(),

"ahb1.sequencer.*", this);

endfunction

endclass

This way we don’t care about the order in which instance overrides get matched, since we only have one set of overrides. The weakness of this approach is that any new behavior test2 defines won’t get inherited by this one.

For these extra instance overrides we had to rely on strings again, which means that if the hierarchy changes, we’ll have one more place to update. We can also achieve the same effect in a different way. If you remember from the previous post, factory overrides are chained. That means that if A is overridden by B and B is overridden by C, then whenever we try to create an instance of A we’ll end up with an instance of C. We can make use of this chaining by setting up the following type overrides:

class test3d extends test2;

`uvm_component_utils(test3d)

function new(string name, uvm_component parent);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

virtual function void end_of_elaboration_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.end_of_elaboration_phase(phase);

write_ahb_item::type_id::set_type_override(fast_write_ahb_item::get_type());

read_ahb_item::type_id::set_type_override(slow_read_ahb_item::get_type());

endfunction

endclass

The advantage of this second method is that we don’t have to rely on instance paths when setting up the overrides. At the same time, if we were to have three interfaces, with two of them being set up to generate read items, then we couldn’t differentiate between the two if we needed to (for example to set one up as fast and the other one as slow). Both approaches have their plusses and minuses, but it’s good to know what is possible and choose between them depending on the situation. We could also create a combination of the two:

class test3e extends test2;

`uvm_component_utils(test3e)

function new(string name, uvm_component parent);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

virtual function void end_of_elaboration_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.end_of_elaboration_phase(phase);

write_ahb_item::type_id::set_inst_override(fast_write_ahb_item::get_type(),

"ahb0.sequencer.*", this);

read_ahb_item::type_id::set_inst_override(slow_read_ahb_item::get_type(),

"ahb1.sequencer.*", this);

endfunction

endclass

By relying on chaining, we don’t have to worry about the order in which instance overrides get matched.

The main problem with instance overrides is their reliance on strings. If the hierarchy changes, we have to update our strings, but unfortunately this is easy to forget. Fortunately, we can mitigate this problem by relying more on the third argument to set_inst_override(…) and less on the second one. Instead of specifying the path to the sequencer as a string that should be appended to the test’s path (passed in as this), we could specify the sequencer as the parent argument directly:

class test3f extends test1;

`uvm_component_utils(test3f)

function new(string name, uvm_component parent);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

virtual function void end_of_elaboration_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.end_of_elaboration_phase(phase);

ahb_item::type_id::set_inst_override(fast_write_ahb_item::get_type(),

"*", ahb0.sequencer);

ahb_item::type_id::set_inst_override(slow_read_ahb_item::get_type(),

"*", ahb1.sequencer);

endfunction

endclass

This way, if we change the way we instantiate our agents (by bundling them in an AHB environment, for example) or their names, we would get compile errors, which are much easier to locate and fix than runtime errors. It’s unfortunate that the set_inst_override(…) function accepts the string path first and the parent component second (and only as an optional argument). This is yet another design flaw, since it promotes string usage. A better decision would have been to require the component argument and allow the string path to be optional, with a default value of ”*“:

static function void set_inst_override(uvm_object_wrapper override_type,

uvm_component parent, string inst_path = "*");

For our fourth and final test, we’ll need to make sure that we only generate byte transfers. The only thing we can do here is to create another set of items which both contain the same additional constraint:

class byte_write_ahb_item extends write_ahb_item;

`uvm_object_utils(byte_write_ahb_item)

constraint byte_sized {

size == BYTE;

}

function new(string name = "byte_write_ahb_item");

super.new(name);

endfunction

endclass

class byte_read_ahb_item extends read_ahb_item;

`uvm_object_utils(byte_read_ahb_item)

constraint byte_sized {

size == BYTE;

}

function new(string name = "byte_read_ahb_item");

super.new(name);

endfunction

endclass

We can set up the overrides, like we did for the previous tests, using either method. In this case, though, per type overrides feel more natural:

class test4 extends test2;

`uvm_component_utils(test4)

function new(string name, uvm_component parent);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

virtual function void end_of_elaboration_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.end_of_elaboration_phase(phase);

write_ahb_item::type_id::set_type_override(byte_write_ahb_item::get_type());

read_ahb_item::type_id::set_type_override(byte_read_ahb_item::get_type());

endfunction

endclass

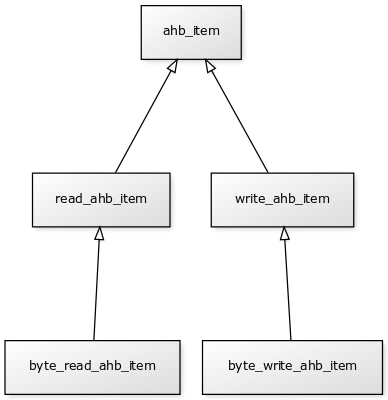

I wanted to show off this last test because, while it does the same thing as its e counterpart, the way we achieved it is fundamentally different. In e we could add the new constraint once and it would apply to all instance of that struct. In SystemVerilog we had to create separate branches in our inheritance tree to be able to differentiate between the two instances:

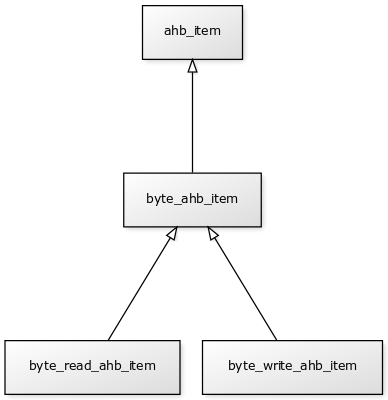

Ideally, to avoid repetition of the byte constraint, the inheritance tree should have looked like this:

At the same time, we still want to have the write_ahb_item and read_ahb_item classes available for the other tests, as well as a simple byte_ahb_item transfer class for some other more random test.

Maybe for such a trivial constraint like making all items byte wide it isn’t worth thinking about this topic, but what about more complicated constraints? Ideally, we should just have one class that defines the constraint of interest (make all items reads, writes, bytes, etc.) and that gets extended whenever needed. But what if we would need to combine more constraints? We’d need to inherit from multiple classes, which we can’t do in SystemVerilog. It’s clear we need a flexible way of managing constraints to avoid duplication and while multiple inheritance isn’t technically possible, we can fake it using the mixin pattern. I’ve already written about how to use this pattern to simplify constraint management, a topic that fits nicely to what we discussed here.

You can find the code for both the e and the SystemVerilog examples (all variants) on SourceForge.

In this couple of posts we analyzed the factory override mechanism in UVM, specifically the ability to globally replace a certain class with one of its subclasses (by using set_type_override(…)) and how to restrict this replacement to parts of the testbench hierarchy (by using set_inst_override(…)). The factory pattern gives us the flexibility of AOP to inject new behavior without touching the original code, but it demands more discipline (objects must be created using the factory) and it requires more code (classes, old and new, must be registered with the factory). Using the factory to add constraints on top of existing sequences and sequence items is a particularly valuable way to specialize tests by guiding the random solver, which allows us to achieve faster coverage closure and find bugs earlier.

Comments